En el ordenador hay instalado un Quiz de 12 preguntas sobre la Fundació Antoni Tàpies (FAT). Cada pregunta consta de 3 posibles respuestas que enfrentan al visitante con su conocimiento del museo. Las respuestas son cruzadas con las de los visitantes precedentes. El visitante no conocerá las respuestas correctas, solamente cuántos visitantes han respondido mejor y peor que él.

POR EJEMPLO:

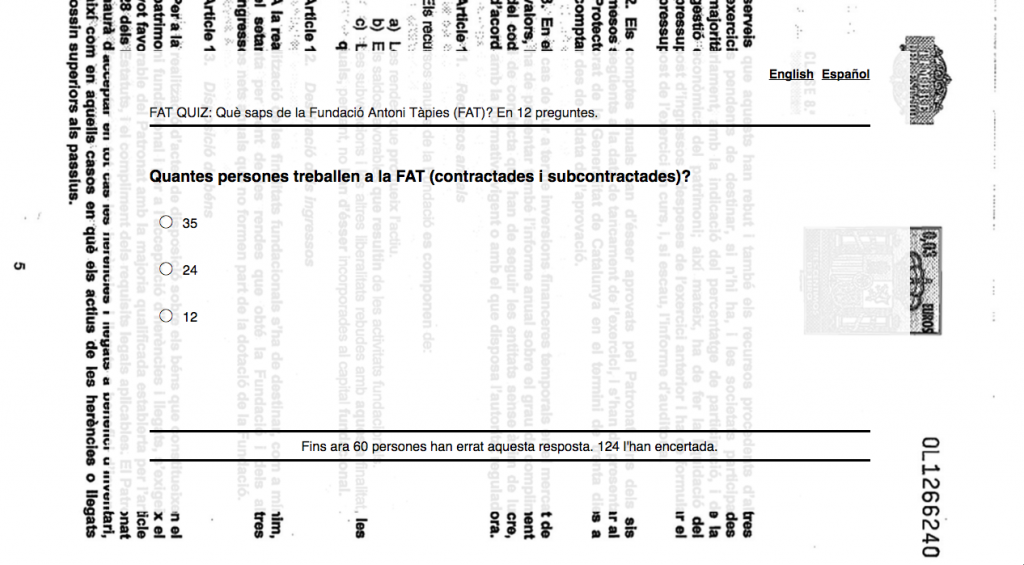

¿Cuántas personas trabajan en la FAT? (Contratadas y subcontratadas)

- 35

- 24

- 12

Hasta ahora 60 personas han errado la respuesta y 124 la han acertado.

EL ESPECTADOR ECLIPSADO

Los museos quieren conocer a su público, lo someten a encuestas y lo invitan a participar. Mailings, carteles y presencia en medios son los cantos de sirena que atraen visitantes. Visitantes que serán registrados, analizados y, en última instancia, monitoreados. El público, sin embargo, no tiene el mismo conocimiento de su interlocutor institucional. Antes de entrar a ver una exposición o a participar de alguna actividad, el visitante no le hace al museo las mismas preguntas que éste le ha hecho. Los públicos son diferenciados por edad, por posición socioeconómica, por procedencia geográfica. Se persigue conocer la identidad de los diferentes públicos que visitan la institución. ¿Pero acaso conoce el público la identidad del museo que visita, su posición socioeconómica en el particular contexto de una ciudad, de un país?

Si bien los museos siguen hoy construyendo la representación del mundo por exclusión –mostrando unas cosas y no otras–, en relación con el público el mecanismo es el opuesto. Es a partir de la inclusión que puede organizarse el dispositivo de identificación y selección al que están llamados los museos. El museo se presenta a sí mismo como una institución integradora, abierta a todos los públicos, y será precisamente esta característica la que legitimará su espacio de poder en el contexto de las distintas instituciones públicas. La inclusión es el fin último de todo dispositivo y por eso mismo se dirige a la opinión pública no sin antes ocultarse tras el mensaje que está llamado a vehicular. El museo tiene la vocación de esconderse, de presentarse a sí mismo como una herramienta a disposición de artistas y visitantes, una herramienta inocua que no interfiere en la comunicación entre ambos. Y sin embargo, el museo ya no se legitima por las obras que exhibe sino por su capacidad de atraer públicos diversos y hacerlos actuar. Cuanta mayor es la participación, más plena es la inclusión de los públicos en el discurso democratizador que los museos enarbolan. Un ciudadano que participa es un ciudadano integrado. De ahí que sea difícil no sospechar que el interés del museo por conocer a sus públicos, por atraerlos y hacerlos participar, no sea una herramienta de integración y, en última instancia, de manipulación.

Proponer al visitante someterse a un Quiz es redoblar los esfuerzos del museo por introducir al público en la lógica de la participación. Pero esta vez el visitante no ha de hablar de sí mismo, no se le pide que regale sus datos que, de todas formas, el museo conocerá monitoreando su teléfono o localizando su dirección de correo. Tampoco se le ofrece una pantomima democrática pidiéndole el voto en un referéndum que, de todas formas, no cambiará nada. Las 12 preguntas del Quiz que aquí proponemos versan sobre la institución que el espectador se dispone a visitar. Es invirtiendo el dispositivo interrogador –no se pregunta sobre la identidad del visitante, sino sobre la del museo– como el visitante desaparece. El visitante ya no recibe el consuelo narcisista de ver su semblante infinitamente reflejado en las pulidas superficies del museo sino que es obligado a mirar un poco más allá de las fachadas acristaladas.

Un Quiz es un cuestionario en el que las preguntas no se hacen en beneficio de quien hace las preguntas, sino del que las responde. Quien desea conocer el resultado de las respuestas es la misma persona que está respondiéndolas y, sin embargo, quien ha elaborado las preguntas es otra persona. Esta operación solitaria, que a nadie importa mas que al propio interrogado, permite que el visitante deje de ser el centro de las miradas. No es el museo que desaparece mientras el visitante participa sino que participando, respondiendo a las preguntas, el visitante hace aparecer la institución. Es sometiéndose conscientemente a la manipulación como el visitante tiene la oportunidad de ausentarse y, ausentándose, apercibir el museo y su dominio.

EQUIPO

Roger Bernat. Programación: Matteo Sisti Sette. Agradecimientos: Marie-Klara González. Una producción de Fundació Antoni Tàpies (FAT) en la exposición How to do things with documents (Performing the Museum) comisariada por Oriol Fontdevila.

Inauguración: 11-11-2015 (19:00h) Fundació Antoni Tàpies. Exposición: 11-11-2015 > 06-12-2015.

DESCRIPTION

Screen, computer with internet connection and mouse. A Quiz with 12 questions about the Fundació Antoni Tàpies (FAT) is installed on the computer. Each question has 3 possible answers. The questions confront the visitor with their knowledge of the museum. The answers are crossed with those of previous visitors. The visitor will not know the correct answers, only how many visitors have answered better and worse than him.

POR EJEMPLO:

How many people work at the Foundation? (Contracted and subcontracted)

- 35

- 24

- 12

So far 60 people have got the answer wrong and 124 have got it right.

THE ECLIPSED SPECTATOR

Museums want to know their public, they submit it to surveys and invite it to participate. Mailings, posters and presence in the media are the siren songs that attract visitors. Visitors who will be recorded, analyzed and ultimately monitored. The public, however, does not have the same knowledge of its institutional interlocutor. Before entering an exhibition or participating in an activity, the visitor does not ask the museum the same questions that the museum has asked. The audiences are differentiated by age, by socioeconomic position, by geographical origin. The aim is to know the identity of the different audiences that visit the institution. But does the public know the identity of the museum they visit, their socioeconomic position in the particular context of a city, of a country?

Although museums today continue to construct the representation of the world by exclusion –showing some things and not others–, in relation to the public the mechanism is the opposite. It is from the inclusion that the identification device of the museums can be organized. The museum presents itself as an integrating institution, open to all audiences, and it will be precisely this characteristic that will legitimize its space of power in the context of the different public institutions. Inclusion is the ultimate goal of any device and for this very reason it addresses public opinion, but not before hiding behind the message it is called upon to convey. The museum has the vocation of hiding, of presenting itself as a tool available to artists and visitors, an innocuous tool that does not interfere with communication between the two. And yet, the museum is no longer legitimized by the works it exhibits but by its ability to attract diverse audiences and make them act. The greater the participation, the fuller the inclusion of the public in the democratizing discourse that museums uphold. A participating citizen is an integrated citizen. Hence, it is difficult not to suspect that the museum’s interest in knowing its audiences, in attracting them and making them participate, is not a tool for integration and, ultimately, for manipulation.

Proposing the visitor to take a Quiz is redoubling the museum’s efforts to introduce the public to the logic of participation. But this time the visitor does not have to talk about himself, he is not asked to give away his data, which the museum will find out anyway by monitoring his phone or locating his email address. Nor is he offered a democratic pantomime asking him to vote in a referendum that, in any case, will not change anything. The 12 questions of the Quiz that we propose here are about the institution that the viewer is about to visit. It is by inverting the questioning device –it does not ask about the identity of the visitor, but about that of the museum– that the visitor disappears. The visitor no longer receives the narcissistic consolation of seeing his countenance infinitely reflected in the polished surfaces of the museum, but is forced to look a little beyond the glass facades.

A Quiz is a questionnaire in which who wants to know the result of the answers is the same person who is answering them. This solitary operation, which nobody cares about more than the person being questioned, allows the visitor to stop being the center of attention. It is not the museum that disappears while the visitor participates, but by participating, answering the questions, the visitor makes the institution appear. It is by consciously submitting to manipulation that the visitor has the opportunity to be absent and, by being absent, perceive the museum and its domain.